Addiction did not begin with modern drugs.

It began with the conditions that made life possible.

Long before brains, cultures, or substances existed, Earth was already running experiments in energy, memory, and control. At volcanic seafloors, minerals and seawater interacted in ways that did not merely release energy — they stored it.

Two researchers, working decades apart, uncovered this forgotten origin.

In the 1980s and 1990s, German chemist Günter Wächtershäuser asked a radical question: what if life did not start in a primordial soup, but on rock surfaces?

He demonstrated that iron and nickel sulfide minerals — common around volcanic vents — could catalyze chemical reactions under early Earth conditions. In laboratory experiments, carbon monoxide reacting with methanethiol on these mineral surfaces produced thioesters: energy-rich molecules central to modern metabolism.

What mattered was not just the reaction itself, but its structure.

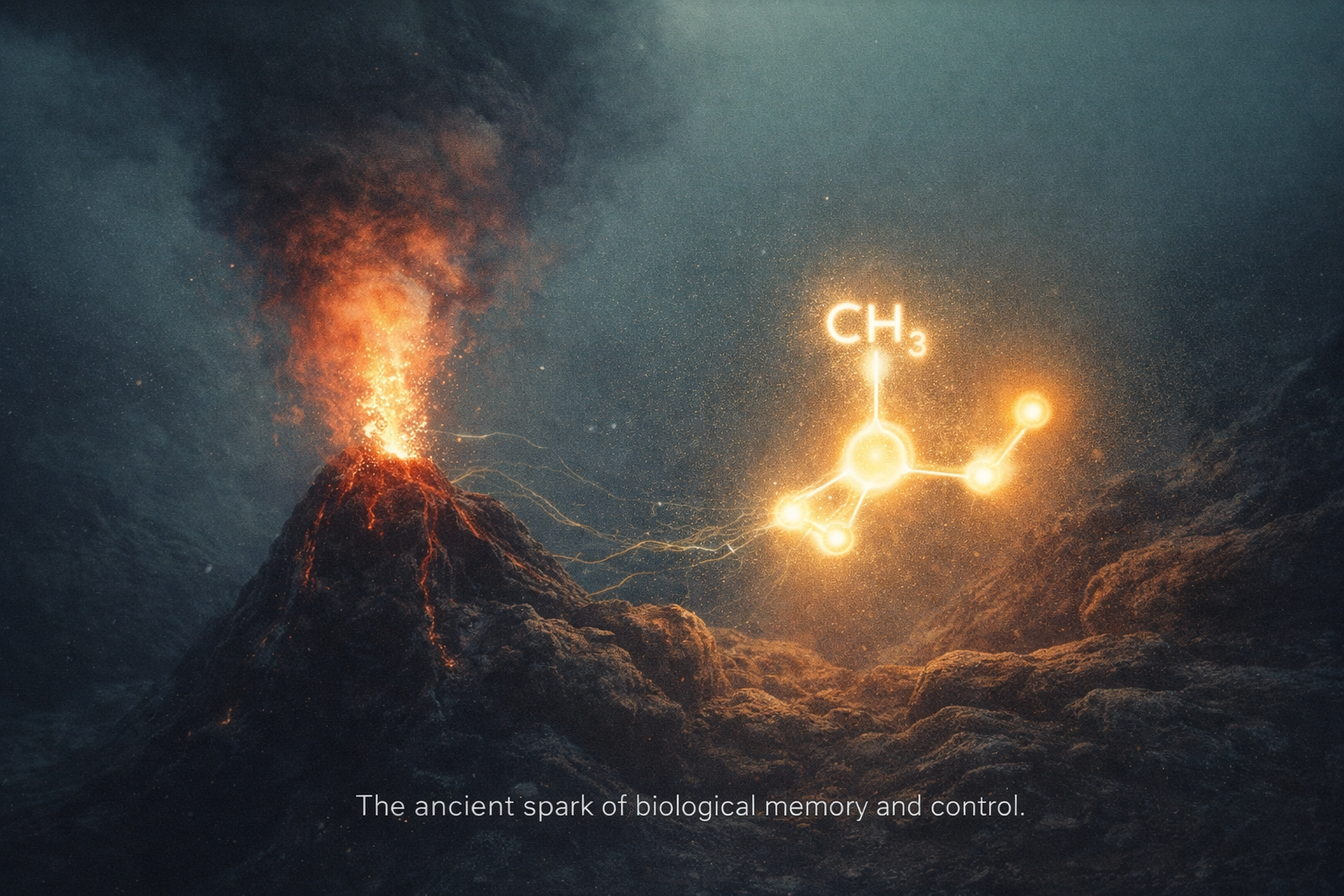

These reactions generated methyl-bearing molecules.

Under natural volcanic conditions, methyl groups (–CH₃) — the same chemical units that now regulate memory, metabolism, and stimulation in living organisms — could form and persist. Wächtershäuser recognized these compounds as primitive energy currencies, predecessors of acetyl-CoA, the central hub of contemporary biochemistry.

At the same time, from a geological perspective, Michael Russell was uncovering another essential piece.

While studying ancient mineral formations, Russell identified fossilized hydrothermal chimneys — structures formed where alkaline fluids from Earth’s crust met the acidic early ocean. Across their thin iron-sulfide walls, natural electrochemical gradients arose.

Earth itself was generating proton gradients.

These gradients functioned like natural batteries, driving chemical reactions repeatedly without external input. Russell proposed that these vents acted as inorganic reactors, sustaining cycles of chemistry long before cells existed.

Taken together, these discoveries point to a single insight: Life did not emerge from randomness. It emerged from repeating energy gradients, mineral surfaces, and methyl chemistry. This matters because the same chemical logic still operates inside us.

The methyl group that once helped store energy on mineral surfaces now regulates gene expression, neurotransmitter synthesis, detoxification, and metabolic timing in the human body. Proton gradients became ATP. Mineral catalysis became enzymatic metabolism. Geological repetition became biological memory.

Methylation is how biology remembers.

It is a chemical note written into cells, telling them what to repeat and what to avoid.

In early organisms, methyl groups acted as survival tools. When stress appeared — heat, hunger, toxins, light — cells marked their DNA, storing molecular memory of experience. These marks determined which genes stayed active and which fell silent. Long before nervous systems existed, life was already learning.

This process began even earlier.

At submarine volcanoes, where iron and sulfur minerals met alkaline hydrothermal fluids and the early ocean, electrical gradients repeated endlessly. Each cycle left a trace. Each trace reinforced the next. From this repetition emerged methyl chemistry — not as symbolism, but as stored chemical information.

When life formed, it carried this system forward.

Methyl groups became biological switches.

They attached to DNA.

They regulated genes.

They shaped neurotransmitters and energy metabolism through the methionine cycle — where sulfur and carbon meet.

As humans evolved, we learned to interact with this system consciously.

Through plants and natural compounds, ancient cultures discovered substances that could alter mood, focus, endurance, and perception. Fermented alcohol, cacao, tea, coffee, cannabis, early tobacco — all of them act, in part, by interacting with methylation-linked signaling.

When these substances enter the body, they do not merely stimulate the brain. They shift methyl balance, altering dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin regulation. The result feels powerful: clarity, drive, connection, relief.

Different substances. Same spark. The methyl group — CH₃.

History reflects this pattern repeatedly.

When societies discover new stimulants, expansion and acceleration follow. When supplies falter or overload appears, instability emerges. This is not coincidence. It is the same memory mechanism replayed at civilizational scale.

Addiction, in this view, is not a moral failure or a modern accident. It is the ancient memory mechanism of life — activated without completion. A biological signal that cannot terminate returns again and again. What once stabilized early life now becomes pathological repetition when driven without resolution.

The problem is not stimulation itself.

It is stimulation without completion.

Until this mechanism is understood at its origin — in gradients, minerals, and methyl chemistry — it will continue to repeat, in bodies and in civilizations alike.