Addictive energy does not begin in the mind.

It begins in a hydrophobic environment.

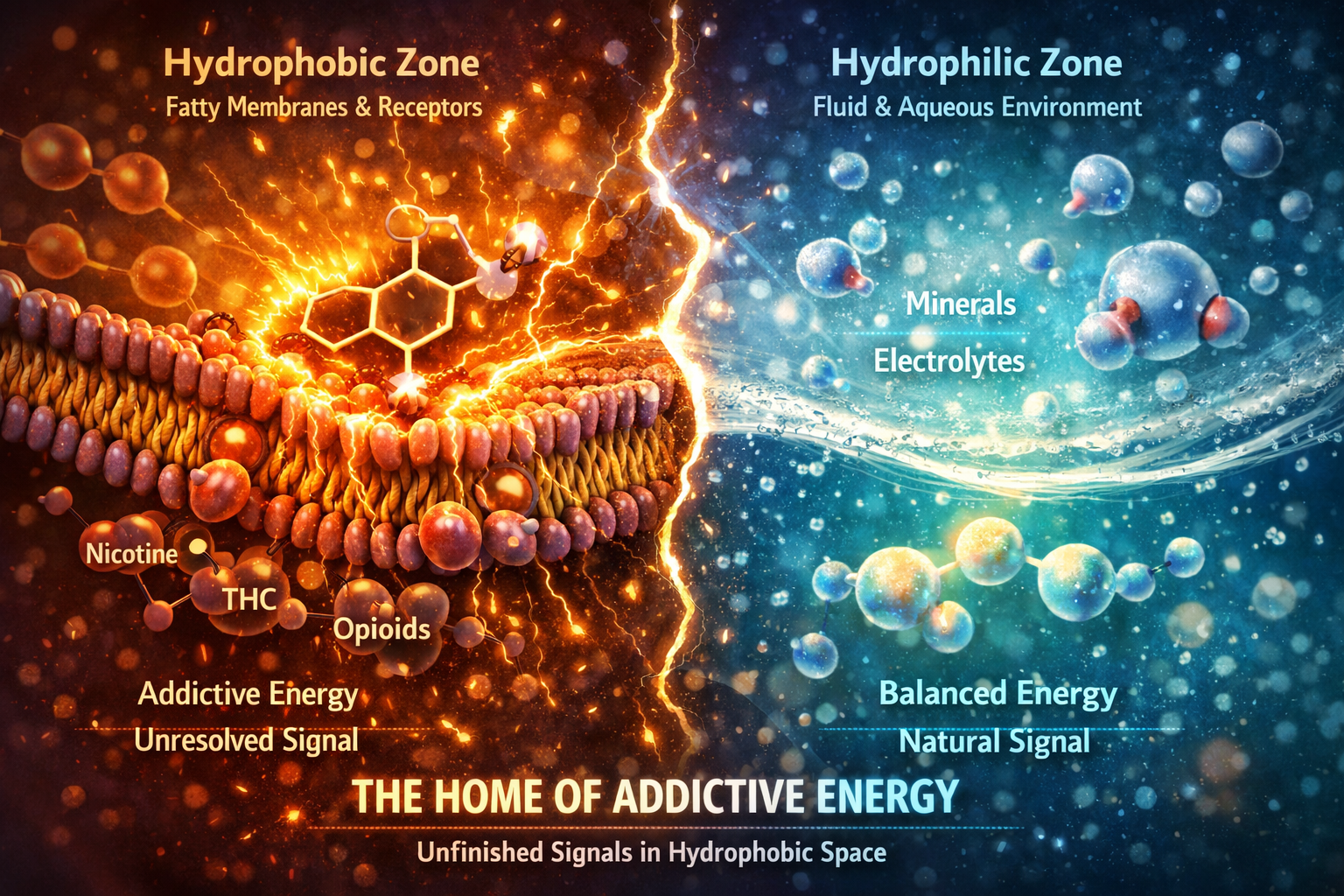

(Hydrophobic means “water-repelling.” These are fatty, oily regions such as cell membranes, receptors, and nervous tissue. Hydrophilic means “water-loving” — the fluid spaces where minerals, electrolytes, and metabolic products dissolve and move.)

Most modern stimulants — nicotine, caffeine, alcohol, THC, antidepressants, opioids, and petroleum-derived compounds — are hydrophobic molecules. They do not circulate freely in water. They move toward fat, membranes, and receptors.

That is their home.

Inside these hydrophobic zones, methyl-carrying compounds lodge directly into biological interfaces. They activate signaling, release energy, and open circuits — but they do so outside the body’s natural timing system. The stimulation arrives, yet completion does not.

Energy is sparked. Resolution is delayed.

This is why the effect feels powerful, immediate, and convincing — and why it fades, returning as urge. In living systems, methyl groups normally support memory, polarity, and coherence when they move through hydrophilic metabolic pathways. Energy is used and then resolved.

But when methyl groups arrive bound to alkaloids, oils, or hydrocarbons, they enter through hydrophobic gates. They excite receptors without providing the mineral timing required for completion.

Nicotine (C₁₀H₁₄N₂) • Carbon • Hydrogen • Nitrogen + Methyl group

Caffeine (C₈H₁₀N₄O₂) • Carbon • Hydrogen • Nitrogen • Oxygen + Methyl group

Alcohol (Ethanol - C₂H₅OH) • Carbon • Hydrogen • Oxygen + Methyl group

Cannabis (Tetrahydrocannabinol, THC – C₂₁H₃₀O₂) • Carbon • Hydrogen • Oxygen + Methyl group

Antidepressant (Fluoxetine – C₁₇H₁₈F₃NO) (active ingredient in Prozac) • Carbon • Hydrogen • Nitrogen • Oxygen • Fluorine + Methyl group

Morphine (C₁₇H₁₉NO₃) • Carbon • Hydrogen • Nitrogen • Oxygen + Methyl group

LSD (Lysergic acid diethylamide – C₂₀H₂₅N₃O) • Carbon • Hydrogen • Nitrogen • Oxygen + Methyl group

Sertraline (C₁₇H₁₇Cl₂N) (antidepressant, Zoloft) • Carbon • Hydrogen • Nitrogen • Chlorine + Methyl group

Cannabidiol (CBD – C₂₁H₃₀O₂) (non-psychoactive cannabis compound) • Carbon • Hydrogen • Oxygen + Methyl group

Petroleum (Crude Oil – mixture of hydrocarbons such as alkanes, cycloalkanes, and aromatics) • Carbon • Hydrogen +Methyl group

Petroleum is not a single substance. It’s a vast mixture of hydrocarbons — methane, hexane, octane, benzene, toluene, xylene — and almost all of them share one small but decisive feature: the methyl group (–CH₃). This tiny chemical unit is central to energy. It carries charge. It sparks reactions. It moves systems.

But what matters is where the methyl group lands.

When methyl groups bind to proteins, fats, or sugars inside living systems, they act as nutrients. They support memory, polarity, and coherence. Energy is used — and then resolved.

When methyl groups bind to alkaloids, oils, or hydrocarbons, the effect is different. They become stimulants. Stimulant-bound methyl groups don’t nourish — they ignite. They activate circuits without completing them.

Nicotine is a clear example. As an alkaloid, its methyl group allows it to lock directly into nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, firing signals that the body was not prepared to resolve. Caffeine works similarly, carrying three methyl groups that block adenosine — the signal for rest — forcing wakefulness instead of recovery.

Morphine and cocaine follow the same principle. Different molecules. Same pattern. The stimulation feels powerful because energy is released. But it fades because the system has nowhere to place it.

This is one of the core distinction explored in this work: energy that nourishes versus energy that overstimulates — not by morality, habit, or willpower, but by chemistry and timing.